'via Blog this'

lunes, 19 de diciembre de 2011

lunes, 12 de diciembre de 2011

10 Innovative Schools Allowing Smartphones in the Classroom

Cell phones have long been a serious no-no in the classroom, and many schools, stating that they are a serious distraction for students, have banned them from campuses altogether. Yet there is a growing trend that is lifting the ban on smartphones and instead asking kids to use their phones and mobile devices as learning tools. While some have responded critically to this movement, others have found that it helps students to become engaged and interested in lessons, and in some districts has even resulted in a marked increase in performance levels.

Whether you're still on the fence about the role of mobile technology in the classroom or are looking for ways to get inspired to use it in your own lessons, it pays to learn a bit more about how smartphones are currently being used for education. Here, we've collected stories about just a handful of the schools leading the way in using smartphones in the classroom, making for both interesting and informative research for any tech-savvy (or tech curious) teacher. Who knows, you may just find ideas that inspire you to initiate a mobile revolution in your own classroom!

-

Onslow County Schools

This North Carolina school district was looking for an innovative way to help close their math achievement gap in some of their economically challenged schools. They decided to try smartphones. It seems that the mobile devices are working, as the school district has seen an improvement in standardized test scores and students using them outpaced others in the district and across the state. The schools participating in the program, called Project K-Nect, use the phones in Algebra, Algebra II, and Geometry, allowing students to use them as calculators or to look up information on the web, watch math videos, and play educational games. Students using the phones reported feeling more confident about their math abilities, were more motivated to take other math courses, and over half are now considering a career in a math field.

This North Carolina school district was looking for an innovative way to help close their math achievement gap in some of their economically challenged schools. They decided to try smartphones. It seems that the mobile devices are working, as the school district has seen an improvement in standardized test scores and students using them outpaced others in the district and across the state. The schools participating in the program, called Project K-Nect, use the phones in Algebra, Algebra II, and Geometry, allowing students to use them as calculators or to look up information on the web, watch math videos, and play educational games. Students using the phones reported feeling more confident about their math abilities, were more motivated to take other math courses, and over half are now considering a career in a math field. -

Cimarron Elementary School

Students in the fifth grade are Cimarron Elementary School are getting the chance to work with smartphones in their classrooms. Phones are issued to the students with the messaging and calling capabilities disabled, but students can still connect to the internet, schedule assignments, and send emails to their teachers through the phones. Students use the phones to do their homework, often on-the-go, and to keep in touch with teachers. The students also use the mobile devices to do web quests, scan QR codes linked to vocab and reading websites, make excel spreadsheets, create quizzes, and even graph their science lab results. The pilot program seems to be doing well, with an increase in students' math and science scores from the previous year.

Students in the fifth grade are Cimarron Elementary School are getting the chance to work with smartphones in their classrooms. Phones are issued to the students with the messaging and calling capabilities disabled, but students can still connect to the internet, schedule assignments, and send emails to their teachers through the phones. Students use the phones to do their homework, often on-the-go, and to keep in touch with teachers. The students also use the mobile devices to do web quests, scan QR codes linked to vocab and reading websites, make excel spreadsheets, create quizzes, and even graph their science lab results. The pilot program seems to be doing well, with an increase in students' math and science scores from the previous year. -

Watkins Glen School District

Watkins Glen School District is taking part in program this fall called Learning on the Go, that puts netbooks, smartphones, and mini-netbooks into the hands of students. The program has been used at the school for two years now, but has only now just expanded to include the use of netbooks and all grade levels at the school. With 40% of the student body not having internet access at home, educators hope that the mobile devices will help to better prepare students for the challenges of an increasingly globalized and digital world, allowing students to gain familiarity with using the web for a wide range of educational tasks.

Watkins Glen School District is taking part in program this fall called Learning on the Go, that puts netbooks, smartphones, and mini-netbooks into the hands of students. The program has been used at the school for two years now, but has only now just expanded to include the use of netbooks and all grade levels at the school. With 40% of the student body not having internet access at home, educators hope that the mobile devices will help to better prepare students for the challenges of an increasingly globalized and digital world, allowing students to gain familiarity with using the web for a wide range of educational tasks. -

St. Mary's City School

St. Mary's School in Ohio is one of the schools leading the way in using smartphones in the classroom. In 2009, the school began providing more than 2,300 third, fourth, and fifth graders with their own PDAs for use in the classroom and at home. Loaded onto the devices are educational programs that allow students to do everything from write an essay to study math through flash cards. Teachers at the school want to embrace mobile technology and help students to understand that mobile devices can be a valuable tool in education, when used right, of course. Students at the school have enthusiastically embraced the program, and many report great excitement at the thought of being assigned their own mobile device.

St. Mary's School in Ohio is one of the schools leading the way in using smartphones in the classroom. In 2009, the school began providing more than 2,300 third, fourth, and fifth graders with their own PDAs for use in the classroom and at home. Loaded onto the devices are educational programs that allow students to do everything from write an essay to study math through flash cards. Teachers at the school want to embrace mobile technology and help students to understand that mobile devices can be a valuable tool in education, when used right, of course. Students at the school have enthusiastically embraced the program, and many report great excitement at the thought of being assigned their own mobile device. -

Edmonton School

While many schools on this list are providing students with their own phones and mobile devices, Edmonton school is taking a different approach to bringing smart phones into the classroom. The school isn't providing phones or other devices but encourages students to bring their own, allowing everything from smartphones to iPads to be used during class time. Students are allowed to employ their phones and tablets as calculators, dictionaries, planners, and even sketchbooks depending on the lesson. The school employs a technology coach as well, who works with teachers to help them better integrate these and other technologies into their curricula. As for students, they love the new rules and many feel lucky to be able to bring their favorite tech devices into the classroom.

While many schools on this list are providing students with their own phones and mobile devices, Edmonton school is taking a different approach to bringing smart phones into the classroom. The school isn't providing phones or other devices but encourages students to bring their own, allowing everything from smartphones to iPads to be used during class time. Students are allowed to employ their phones and tablets as calculators, dictionaries, planners, and even sketchbooks depending on the lesson. The school employs a technology coach as well, who works with teachers to help them better integrate these and other technologies into their curricula. As for students, they love the new rules and many feel lucky to be able to bring their favorite tech devices into the classroom. -

Crosby-Ironton High School

Most teachers don't allow cell phones to be used in the classroom, but high school science teacher Bob Kuschel isn't most teachers. Kuschel permits students to use their smartphones in his class, and says he finds them to be an effective learning tool for students. For the past three years, he has allowed phone usage while students are working on labs or class assignments, though the phones must be put away during lectures. Kuschel believes that it's important for students to be able to access information easily and reports that allowing students to use them has not only improved grades but also student interest in their coursework.

Most teachers don't allow cell phones to be used in the classroom, but high school science teacher Bob Kuschel isn't most teachers. Kuschel permits students to use their smartphones in his class, and says he finds them to be an effective learning tool for students. For the past three years, he has allowed phone usage while students are working on labs or class assignments, though the phones must be put away during lectures. Kuschel believes that it's important for students to be able to access information easily and reports that allowing students to use them has not only improved grades but also student interest in their coursework. -

Southwest High School

This North Carolina high school is also taking part in Project K-Nect, a pilot program that's working to bring smartphones into the classroom with the hope that it will improve test scores and help students at some of the states most under-funded schools. Sponsored by Qualcomm, the project is providing smartphones for a few trial courses, though it could be expanded in coming years. Administrators at the school hope that the phones will not only improve scores, but help to better prepare students for using new technologies, as many in the district don't have access to the internet or a computer at home. So far, the program seems to be working. A study found that students with the phones performed 25% better than their classmates on an end-of-year algebra exam. Yet teachers report that the phones have a downside, too, as teachers must spend a good deal of time monitoring how the students are using them in their hours away from school.

This North Carolina high school is also taking part in Project K-Nect, a pilot program that's working to bring smartphones into the classroom with the hope that it will improve test scores and help students at some of the states most under-funded schools. Sponsored by Qualcomm, the project is providing smartphones for a few trial courses, though it could be expanded in coming years. Administrators at the school hope that the phones will not only improve scores, but help to better prepare students for using new technologies, as many in the district don't have access to the internet or a computer at home. So far, the program seems to be working. A study found that students with the phones performed 25% better than their classmates on an end-of-year algebra exam. Yet teachers report that the phones have a downside, too, as teachers must spend a good deal of time monitoring how the students are using them in their hours away from school. -

Mounds View High School

Students at this Twin Cities school got a chance to bring some of their favorite technologies into the classroom this fall. The school is allowing students to use personal electronic devices in the classroom, including smartphones, PDAs, and tablet computers. While the school acknowledges the potential drawbacks of allowing tech in the classroom, they think the educational opportunities outweigh the risks. They may be setting a model for schools in the region, as the Minneapolis School District just approved a similar measure for bringing tech into the classroom.

Students at this Twin Cities school got a chance to bring some of their favorite technologies into the classroom this fall. The school is allowing students to use personal electronic devices in the classroom, including smartphones, PDAs, and tablet computers. While the school acknowledges the potential drawbacks of allowing tech in the classroom, they think the educational opportunities outweigh the risks. They may be setting a model for schools in the region, as the Minneapolis School District just approved a similar measure for bringing tech into the classroom. -

Lincoln Middle School

Three sixth grade classrooms are taking on a trial program at this middle school, allowing mobile devices into the classroom. Given phones through a donation by Sprint, educators are now using them in sixth grade science courses. Students use them to graph, track the results of their experiments, write essays, and even look up information on the web. The phones don't offer students free will, as the texting and calling features are disabled, and internet access is limited and closely monitored, but that's OK with students. A study of the phone usage at school showed that they increased the level of student engagement and motivated more students to complete assignments. While the district doesn't have the budget to purchase more phones at the moment, teachers say they'd love to see the program expand.

Three sixth grade classrooms are taking on a trial program at this middle school, allowing mobile devices into the classroom. Given phones through a donation by Sprint, educators are now using them in sixth grade science courses. Students use them to graph, track the results of their experiments, write essays, and even look up information on the web. The phones don't offer students free will, as the texting and calling features are disabled, and internet access is limited and closely monitored, but that's OK with students. A study of the phone usage at school showed that they increased the level of student engagement and motivated more students to complete assignments. While the district doesn't have the budget to purchase more phones at the moment, teachers say they'd love to see the program expand. -

Byron High School

Students at this high school no longer have to hide their phones to use them in class. The school is now allowing phones, laptops, MP3 players, and iPads in the classroom, provided students have the OK of their teachers to use them. Over the five months the program has been in place, the school hasn't seen in increase in students cheating or misusing the technology, perhaps because students are afraid of losing their right to use the tech in the classroom. As of this fall, the program expanded to include the entire school, a change which the school hopes will help not only students but their bottom line as well. Students who are able to bring their own technology to school can help reduce the costs of maintaining a computer lab on campus, and making it easier for students to take notes and look up information is a great added benefit.

Students at this high school no longer have to hide their phones to use them in class. The school is now allowing phones, laptops, MP3 players, and iPads in the classroom, provided students have the OK of their teachers to use them. Over the five months the program has been in place, the school hasn't seen in increase in students cheating or misusing the technology, perhaps because students are afraid of losing their right to use the tech in the classroom. As of this fall, the program expanded to include the entire school, a change which the school hopes will help not only students but their bottom line as well. Students who are able to bring their own technology to school can help reduce the costs of maintaining a computer lab on campus, and making it easier for students to take notes and look up information is a great added benefit.

10 Innovative Schools Allowing Smartphones in the Classroom

jueves, 1 de diciembre de 2011

Agradecimiento y queja

Ayer la Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero festejó un aniversario más de su Autonomía. Con motivo de ello hubo actividades múltiples en varias ciudades y tuve la fortuna de ser invitado a dar una charla en el Auditorio del Palacio de la Cultura del Estado. Me dijeron que mi plática comenzaría a las diez de la mañana y que tendría una hora disponible.

Así fue, llegué a las diez y el recinto aparecía vacío, nadie que informara nada. Pasó casi una hora antes de que algún empleado abriera las puertas al público conformado por estudiantes de bachillerato que esperaban para las charlas, sobre todo mi tema que atraía el interés de sus maestros: "Internet en la Educación".

Yo habia entrado incluso al Auditorio y estuve en el presidium aguardando la hora de inicio. Una hora después ingresó alguien de mi Universidad diciendo abriendo las puertas y diciendo a todo mundo que "se canceló la primera conferencia" (la mía) y que solamente habria la segunda conferencia (de un alto funcionario de la Universidad) que estaría por llegar.

Entonces le dije que yo estaba alli desde las diez, que nadie me dijo que se cancelaría y que la Directora de Investigación me habia advertido que se demoraria el inicio pero que si se daría mi conferencia, la primera, y que estarian en el evento ella y varios funcionarios de la Universidad en el presidium y en las dos filas primeras de asientos que estaban apartados para ello.

Pues no llegó nunca ningún funcionario, solamente el Secretario General de la Universidad, amigo mio, para su charla, le comente lo que sucedía y se disculpó diciendome que tenía motivos para utilizar mi tiempo y que no tenía tiempo de esperar, los motivos eran ciertos, además yo nunca me opondria a cambiar de turno, cualquiera fuere el motivo, pues estaba feliz de ser considerado y podre hablar sobre lo que hago, mi pasión.

Como no llegó nadie nunca más, mi amigo me pidió que leyera su currículum y lo presentara, con mucho gusto lo hice, quiero a mi amigo, recuerdo que ambos haciamos el Doctorado al mismo tiempo en la ciudad de México, él en la UNAM y yo en CINVESTAV-IPN, lo visité en la UNAM, hablamos de realizar después algún trabajo juntos, aunque nunca se concretó y mi amigo entró a la política Universitaria donde se ha desempeñado además de su labor como investigador y docente.

Pues mi amigo impartió su charla a los estudiantes de bachillerato que estaban en el Auditorio, muy interesante su plática sobre problemas de contaminacion y la capa de ozono y su impacto en las construcciones y los sismos que padecemos en la entidad.

Al terminar se disculpó y se fue. Los alumnos se querían salir y abandonaron el sitio pero la Maestra de un grupo de ellos los obligo a regresar para mi charla que parecia ya no iba a darse pues el sitio se quedaba vacío.

La Maestra dijo "Sí. Venimos a la charla". Me presenté rápidamente solo dije mi nombre y comencé la charla. Quería hablar del sentido de la presencia educativa que nos ha proporcionado la Internet, Que la llamada Educación a distancia ha terminado por integrarse a la Educación presencial y que ahora todo aparece como una nueva presencia educativa, alumno(s)-Maestro(s)-Institución.

Hablé de cifras impactantes en el uso de Internet y Redes Sociales y la poblacion mundial. Cómo aprendemos (neurociencias), consecuencias del uso de Internet en la infraestructura educativa (real y virtual), en la Educación (pedagogia conectivista), y un ejemplo, el curso masivo y experimental con 170,000 alumnos impartido por Peter Norton y Sebastian Thrun de la Universidad de Stanford, mismo en el que participo con un gran interés por lo que significa.

Terminé, nunca apareció ningún funcionario, los chicos salieron huyendo ya era tarde, salí del recinto solo y vi al Rector y a su sequito de acompañantes recorriendo la plaza. Recorrí algunos stands conmemorativos. Me fui solo de allí. No llegó a mi charla ningún amigo ni estudiante. No me quejo. Solo escribo la reseña. En mi Universidad se improvisa y estas cosas suelen suceder.

Yo feliz de haber tenido la oportunidad de hablar sobre mis temas de estudio y trabajo. Muchas gracias chicos por su paciencia. Muchas gracias por invitarme a dar esta charla, a veces imagino que por mis polémicas charlas conocidas en la radio universitaria sobre el uso de Internet en la Educación, no quiso ningun funcionario relacionado con el tema entrar, pues he sido ignorado sistemáticamente incluso por mis propios colegas, acostumbrados a la pasividad y a obedecer sin preguntarse nada, a adaptarse a la politica educativa, a llenar formatos para obtener ingresos que mejoren sus salarios a publicar en sitios, donde, cuando y como lo deciden los funcionarios de arriba, a vivir de muertito sin levantar la voz.

Gracias!

Agradecimiento y queja

domingo, 25 de septiembre de 2011

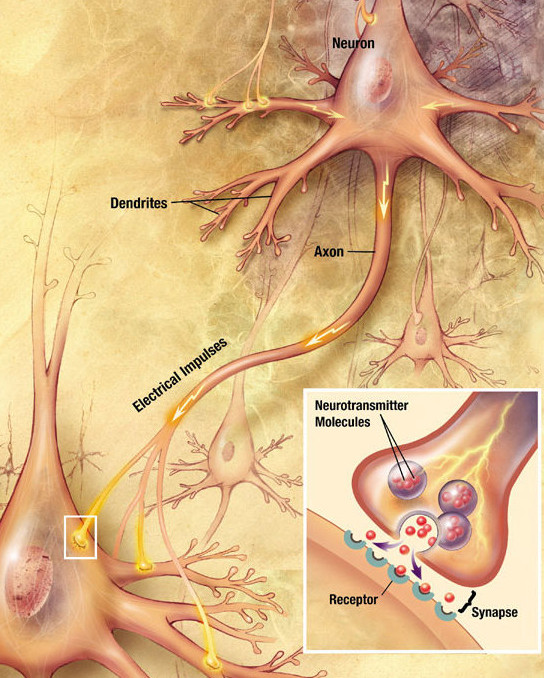

Neurobiological basis of learning and memory (1)

1. Knowledge Codification

2. Knowledge Storage

3. Knowledge Retrieval.

So, Learning depends on the modification of connections between nerve cells.

See for example the Hebbian learning theory, "Cells that fire together, wire together":

"Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity (or "trace") tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability.… When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A's efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased."

The Hebbian learning is a particular case of "associative learning", in which simultaneous activation of cells leads to pronounced increases in synaptic strength between those cells.

How can we understand the process of Knowledge codification?

Neurobiological basis of learning and memory (1)

viernes, 23 de septiembre de 2011

viernes, 16 de septiembre de 2011

Aprendizaje Conectivista (1)

Estar conectados cambia el aprendizaje.

Cuando las conexiones son globales, la experiencia para desarrollar conocimiento se altera dramàticamente.

Durante los ùltimos cuatro años, un creciente nùmero de educadores ha comenzado a experimentar con los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje con el objeto de responder a cuestiones crìticas:

¿còmo cambia el aprendizaje cuando los lìmites formales se reducen?

¿Cuàl es el futuro del aprendizaje?

¿Què tipo de instituciones necesita la sociedad para responder al hiper crecimiento del conocimiento y la ràpida diseminaciòn de la informaciòn?

¿Còmo cambian los roles de los aprendices y educadores cuando el conocimiento està presente en todas partes a un mismo tiempo, es omnipresente?

Experimentando con respuestas a estas preguntas ha generado lo que ahora es conocido como Cursos Masivos Abiertos y En Lìnea.

El conocimiento existe en red. Incrementar el conocimiento consiste en incrementar la conectividad y la diversidad.

Notas rescatadas de: http://change.mooc.ca/

Aprendizaje Conectivista (1)

jueves, 25 de agosto de 2011

Inteligencia Artificial y Conectivismo, una primera aproximación

Inteligencia Artificial

Hace un año en una charla en la Universidad Libre de Bogotá que titulé "La importancia de llamarse Inteligencia Artificial" reflexionaba sobre el papel relevante que tiene nuestro campo de estudio en la evolución de la Web. Esta expectativa puede enmarcarse en cuatro etapas:

1992-2000 Aparece la Web y mediante hipertexto e hiperenlaces la información representada sobre todo por las páginas web se conecta entre sí. Decimos: la Web conecta información.

2000-2010 Aparece el Software Social, la Web conecta a la gente. Se estima en dos mil millones de habitantes conectados. El fenómeno de redes desborda las proyecciones y aún ahora reconocemos que nos falta mucho para entender este fenómeno y sus alcances en la evolución de la modernidad.

2010-2020 Se espera la evolución a un primer plano de lo que hemos dado en llamar la Web 3.0 o Web Semántica. La Web, una vez más. Ahora conecta Conocimiento. Los sitios Web se conectan e interactúan entre sí para resolver nuestros problemas de información y búsquedas mediante agentes inteligentes y la aplicación de algoritmos de razonamiento automatizado, almacenamiento y procesamiento automático de conocimientos. La Web conecta conocimientos y el papel de la Inteligencia Artificial es relevante.

2020-2030 La MetaWeb. La Web conecta inteligencias. La Web actúa como un cerebro enorme al que podemos preguntar. Se estima que existen más de cien mil millones de páginas web y un cerebro humano contiene cien mil millones de neuronas. Cada neurona del cerebro puede conectarse hasta con diez mil neuronas por lo que las sinapsis o conexiones neuronales pueden ser de un tamaño de miles de billones de sinapsis. Si existen en Internet más páginas Web que neuronas en un individuo podemos pensar en una Web como un cerebro artificial, con la salvedad de que la redes neuronales humanas solo podemos estudiar su comportamiento y estructura, en cambio las redes de Internet podemos construirlas y ordenarlas. Pero algunos científicos ya piensan en conectar el cerebro con la Web, lo cual hemos realizado ya pero indirectamente. Usamos la Web para almacenar información.

En cuanto a la enseñanza de la Inteligencia Artificial en las Universidades, los que enseñamos o estudiamos esta disciplina recordamos el primer libro clásico de Elaine Rich que divide el estudio de la Inteligencia Artificial en tres grandes bloques:

Solución de Problemas

Representación de Conocimientos

Aplicaciones

El estudio de la Inteligencia Artificial trae aparejado la discusión de tres grandes problemas científicos que no parecen nunca resolverse:

Aprendizaje

Conocimiento

Inteligencia

El problema es tal que algunos hemos optado por aceptar redefinir estos conceptos en términos de lenguaje de máquinas. Qué significa Aprender para un artefacto, Conocimiento e Inteligencia. En contraposición contra estos mismos conceptos aplicados a la individualidad humana.

Conectivismo

El Conectivismo (que no conexionismo) es propuesto por George Siemens en 2004 como una nueva teoría para explicar el aprendizaje en la era de Internet, esto involucra también el conocimiento. Es decir, integra las redes de Internet, el conocimiento se entiende como un patrón particular de relaciones y el aprendizaje como la creación y mantenimiento de nuevas conexiones y patrones en similaridad con la aproximación coneccionista de las redes neuronales humanas.

El Conectivismo ha venido a reanimar las discusiones anteriores sobre lo que entendemos por Aprendizaje, Conocimiento e Inteligencia.

¿Pueden las redes de Internet Aprender, Conocer y ser Inteligentes? ¿Cómo podemos realizar estos constructos en la red, manipularlos y construir una Web que funcione como un cerebro humano? ¿Cómo podemos contribuir los que hacemos Inteligencia Artificial, en este arduo pero emocionante y fantástico camino?

Inteligencia Artificial y Conectivismo, una primera aproximación

miércoles, 24 de agosto de 2011

El recuento de los daños (1)

Hace casi 34 años comencé a dar clases en una Universidad. En la ciudad de México. En la entonces nueva ENEP-Acatlán. Aún lo recuerdo: Sistemas de Alcantarillado. Tercer año de la licenciatura en Ingeniería Civil. El primer día de clases fue dificil llegar. Vivía en el sur y desconocía el norte. Hacía frío, como hoy. Tomé un transporte que me dejó en una gran avenida. Después caminé y caminé. Hasta dar con el edificio, llegué preguntando. Un chico que me orientó se quedó mirándome extrañado. El también era estudiante y se veía motivado. "¿A qué carrera te inscribiste?" -preguntó curioso. "Soy profesor" -respondí. Claro, estaba orgulloso, no era exactamente profesor, sino sustituto. "Doy un Curso en Ingeniería Civil" -añadí. Y el chico comentó entre sorprendido y alegre: "¿Profesor? ¡Eres muy joven!".

Llegué al área de profesores y tomé una tarjeta para perforar mi registro de llegada a clases. En realidad no era profesor. Cursaba la misma licenciatura en el sur, en la UNAM. El titular de Sistemas de Alcantarillado me enviaba a mí a dictar sus cursos en el norte. En lugar de tomar clase con él, la impartía en el norte, donde era conocido con su nombre, me hacía llamar como él, usurpaba su identidad.

Pero yo estaba feliz enmedio del frio y la neblina, de aparecer como profesor y de pararme enfrente de los estudiantes motivados igual que yo para recibir uno de sus nuevos cursos. Y claro, estaba seguro de impartir una muy buena clase. Mi profesor de la UNAM trabajaba en el gobierno federal, como evaluador de proyectos de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado. Yo era su ayudante en mi tiempo libre. Los fines de semana me la pasaba en su casa por el rumbo del Estadio Azteca trabajando en armar nuevos proyectos, dibujar planos, escribir reportes y proyectar nuevos diseños que después él pasaría por las dependencias con otro nombre, pues él mismo sería evaluador.

En la UNAM era su alumno favorito. Cargaba sus planos, revisaba los proyectos de mis compañeros, asesoraba y resolvía dudas, tomé dos cursos con él y no necesitaba cursar el de Alcantarillado, lo conocía de cabo a rabo, podía impartirlo. Y lo hice.

Hoy, como todos los años, ingreso con melancolía en mi estudio, preparo café y escucho música para tranquilizarme mientras me conecto a la Internet y preparo mis clases. En la Universidad me esperan nuevos estudiantes que ya se han comunicado conmigo para preguntar. Están motivados y desean saber de nuevos libros, horarios de clase y si estaré en la Facultad. Estaré. Pero es un punto de reflexión. Para recordar. Y lo comparto con ustedes.

El recuento de los daños (1)

domingo, 21 de agosto de 2011

Finlandia y el problema de los rechazados en la Universidad de Guerrero

Finlandia y el problema de los rechazados en la Universidad de Guerrero

jueves, 18 de agosto de 2011

Trabajar de 9 a 5 no es la mejor forma de ganarse la vida

Cada día que pasa estar casi ocho horas en un cubículo compartido en la Universidad es mas bien una tontería. Ésto lo presentí desde los primeros años en que comencé a trabajar en la Facultad y era una especie de pesadilla, tanto como cuando era estudiante como cuando llegué a formar parte de la planta docente. Los profesores acostumbran platicar en los pasillos y en los cubículos y en cualquier parte del campus. Charlas ligeras y mundanas que me hacían sentir que estábamos acribillando el tiempo. Pero no podía decir no. Las bromas y el humor mexicano hacían llevadero un tiempo gastado en no hacer nada productivo. Si me encerraba en el cubículo siempre había alguien de dentro o fuera de la Universidad que llegaba a comentar algo, a pedir favores que mas bien parecían pretextos para convivir con uno. Era la vida académica en la Universidad. Y aún lo es.

La inspiración, la creatividad, la imaginación, la concentración, las ideas nuevas suelen venir a diferentes horas, no importa si es día festivo, hora inhábil o medianoche. Uno suele trabajar a esas horas y revisar apuntes, reflexionar y preparar las clases y sobre todo, investigar. Mas hoy en día cuando Internet está presente todo el tiempo y cuando hay gente siempre en los foros y redes sociales compartiendo ideas en forma síncrona y asíncrona. El mundo es redondo y siempre encontramos una Internet dinámica. Contenidos y servicios en la nube a toda hora.

Aún recuerdo cuando comencé a dar un curso de Procesamiento de Datos en el recién inaugurado Tecnológico de Chilpancingo, aún sin campus ni edificios propios, basado en un libro hermoso y caro que había comprado en una librería americana de la ciudad de México. Charlaba con los estudiantes sobre el teletrabajo. Les decía que algunos de ellos posiblemente se toparían con esta opción cuando estuvieran en el mercado de trabajo. De ello hace treinta años. Algunas de mis estudiantes accedieron con el tiempo a empleos importantes en el gobierno del estado.

Lisa Nielsen concluye en su artículo que en este siglo XXI no debemos continuar haciendo las cosas como en los viejos tiempos, no tiene sentido. No existe razón alguna, al orden económico establecido le conviene que todo permanezca igual, tienen el control, podemos innovar siempre y cuando las innovaciones no afecten el orden del mundo. Asi es nuestra educación. Podemos discernir sobre el modelo de competencias y proponer mejoras, criticar pero no cambiar. Eso nos hace creer que somos creativos y críticos en la educación. Podemos hablar de lo que establecen pero no pensar más allá.

Esto no es innovación.

Trabajar de 9 a 5 no es la mejor forma de ganarse la vida

martes, 16 de agosto de 2011

70,000 Students Flock to Free Online Course in Artificial Intelligence | Observations, Scientific American Blog Network

70,000 Students Flock to Free Online Course in Artificial Intelligence | Observations, Scientific American Blog Network

Stanford 'Intro To AI' Course Offered Free Online - Slashdot

Stanford 'Intro To AI' Course Offered Free Online - Slashdot

Virtual and Artificial, but 58,000 Want Course - NYTimes.com

Virtual and Artificial, but 58,000 Want Course - NYTimes.com

Un curso con mas de 58000 estudiantes en línea.

A pesar de tener la formación de Inteligencia Artificial (Doctorado) y dedicarme ahora al estudio del Conectivismo, éste curso será observado por muchos educadores y pensadores porque plantea muchas interrogantes y el curso en sí mismo sera un desafio tanto para los organizadores como para los estudiantes. Desafío pedagógico, didáctico, tecnológico. Una de las razones del interés que ha provocado reside en la popularidad de Peter Norvig quien junto con Stuart Russell han publicado un libro de texto sobre Inteligencia Artificial que es usado en mas de 100 paises y por mas de 1200 Universidades. Los autores tuvieron la idea hace mas de diez años de crear una pagina Web para centralizar recursos existentes como apoyo al libro y al curso que se pretendía impartir.

El Curso que se ofrecer en linea a partir del 10 de octubre sera en Inglés y se denomina Introduction to Artificial Intelligence y para inscribirse solo es necesario registrar un nombre de usuario y una cuenta de correo electrónico. Pues bien, estamos de plácemes y continuare registrando algunas opiniones conforme este evento tan importante para el futuro de la Educación vaya en camino.

Un curso con mas de 58000 estudiantes en línea.

lunes, 15 de agosto de 2011

¿Qué va primero, el huevo, la gallina o ambos?

Esta discusión no es exclusiva en nuestro entorno tercermundista. Existe en todo el mundo. Encuentro por ejemplo este post "Pedagogy Versus Technology" (hoy) en un blog en el Reino Unido http://dougwoods.co.uk/blog/pedagogy-versus-technology/

El post hace referencia al siempre vivo debate entre Pedagogía y Tecnología. ¿Qué fue primero, el huevo o la gallina? En mi Universidad aún existen muchos profesores que reniegan quizá con justa razón su reticencia a tomar en serio ambas cosas: ni pedagogía ni tecnología. La razón que antes no habia entendido se resume a una justificación que me parece válida: los profesores Universitarios estudiamos un posgrado, Maestría o Doctorado, no para ser profesores sino para desarrollarnos como Ingenieros, Biólogos, Abogados, Economistas, Sociólogos, Filósofos, Médicos, Contadores, etc.

De allí la reticencia a invertir tiempo en el estudio de la didáctica y el uso de tecnologías. Aún recuerdo otro debate abierto: ¿deben los profesores Universitarios estudiar algún diplomado o posgrado en Didáctica antes de poder ejercer la docencia en la Universidad? El solo hecho de mencionarlo causa molestia a muchos profesores cuyo quehacer académico no tiene aparentemente nada que ver con la pedagogía.

Es común escuchar a mis colegas responder amablemente cuando son cuestionados: "Si necesitara aplicar alguna teoría pedagógica o tecnología particular en mis Cursos, las utilizaría no tengas duda, pero no lo requiero ahora, no lo necesito, mis Cursos funcionan bien así".

¿El uso de la tecnología debe estar supeditada a una pedagogía particular o no es necesario? ¿Se puede aplicar la tecnología en un determinado Curso sin ligarla a ninguna pedagogía? Los profesores que trabajan en Educación suelen evitar el debate y centrarse solo en la pedagogía, en cambio los profesores que no trabajan en Educación y aplican la tecnología en las aulas suelen ignorar la pedagogía.

En la década de los ochentas, lo recuerdo porque incluso participábamos en rifas de mini computadoras de escritorio y la Universidad era intermediario para la compra a crédito de equipos de cómputo por parte de los docentes, la tecnología era única y estándar: una minicomputadora y un deseo de experimentar qué se podría hacer con ella para la educación y el uso personal. Entonces parecía existir un acuerdo tácito e indiscutible. Ahora no.

Pues que volvermos a clases y el debate continúa. Los profesores formados sin usar tecnología continuarán su labor en la forma acostumbrada y los futuros profesores formados usando tecnologías de Internet seguramente las utilizarán en sus Cursos a pesar de la opinión de las autoridades académicas que siempre van detrás de todas las innovaciones en la educación hasta que no les queda más remedio que aceptarlas.

¿Qué va primero, el huevo, la gallina o ambos?

domingo, 14 de agosto de 2011

MOOC y MOOCC

Proximamente en los siguientes meses se anuncian mas cursos masivos en linea como CHANGE MOOC, CMC y especialemente Introduction to AI Online que ofrecerá la Universidad de Stanford a través de personalidades como Peter Norvig coautor del libro sobre AI más utilizado y conocido en el mundo y libro de texto en mas de cien paises: Artificial Intelligence, a Modern Approach con la tercera edición del libro cuyos autores han tenido la visión de tratar de conformar una comunidad mundial desde hace casi diez años alrededor del uso del libro y de la Inteligencia Artificial como campo de estudio y aprendizajes. Y Sebastian Thrun, un joven y prominente investigador de Stanford.

El lanzamiento de este curso en la modalidad MOOC ha provocado una extensa discusión en Internet sobre el uso del término MOOC. Dave Cormier había divulgado algunos excelentes videos para explicar la filosofia de un MOOC, pero estrictamente hablando el acrónimo MOOC quiere decir Massive Open Online Course y varias Universidades, especialmente Stanford pueden legítimamente utilizar el término MOOC para denominar algunos cursos que ofrecen en la modalidad a distancia, libres (gratuitos) y masivos.

Debido a ello y atendiendo a los cursos MOOC que han facilitado los investigadores George Siemens, Dave Cormier, Stephen Downes entre otros, el sentido inicial de estos cursos es la puesta en práctica de la teoria conectivista para estudiar y discutir el uso de las redes de Internet para aprender y conocer de una forma amplia, democrática, libre, colaborativa, participativa, abierta y distribuida. Creo que una posibilidad de denominacion para evitar confusiones es entender este tipo de cursos MOOC como MOOCC, Massive Open Online Connectivist Courses. Es decir, la práctica connectivista en formato MOOC.

De esta forma podemos entender al menos por ahora, la diferencia entre un MOOC en la educación tradicional a distancia (formal) y un curso conectivista MOOC (informal?) sobre cualquier otra disciplina, asi, podriamos tener en perspectiva cursos sobre Inteligencia Artificial MOOCs o MOOCCs.

En particular señalo que el año pasado intentamos incidir en la creación de una comunidad latinoamericana de aprendizajes y práctica de la Inteligencia Artificial para apoyar inicialmente los cursos formales que se imparten en dos Universidades de Colombia y México, primero a través de un sitio Moodle (http://cerv.biz/moodle1/) y después utilizando videoconferencias (dimdim.com), Blogs, Wikis y Facebook.

Sin embargo, este esfuerzo ha sido insuficiente, aunque debo añadir que la Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia) y la Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero (México) nos proponemos insistir para el próximo año 2012 un nuevo intento. Muestra de ello es el Congreso Anual que estableceremos (un año en cada país) y que tendrá lugar este mes de septiembre en Bogotá, Colombia (http://gemini.udistrital.edu.co/comunidad/grupos/iaft/CongresoUDA2011/) y el próximo año 2012 en Acapulco, México.

Claro estamos muy lejos del nivel del Curso ofrecido por la Universidad de Stanford, el cual consideramos que será un acontecimiento muy importante para la nueva educación superior soportada por los medios sociales de Internet y del cual esperamos formar parte para aprender no solo de Peter Norvig, autor del libro que utilizamos en nuestras aulas sino de la forma en que se desarrollará el curso para renovar nuestros esfuerzos en la búsqueda de la conformación de comunidades globalizadas hispanohablantes con una práctica conectivista en campos de la educación superior necesarios para promover la innovación educativa.

MOOC y MOOCC

lunes, 8 de agosto de 2011

Education

Education Needs a Digital-Age Upgrade

By VIRGINIA HEFFERNANVirginia Heffernan on digital and pop culture.

Tags:

Chances are just that good that, in spite of anything you do, little Oliver or Abigail won’t end up a doctor or lawyer — or, indeed, anything else you’ve ever heard of. According to Cathy N. Davidson, co-director of the annual MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Competitions, fully 65 percent of today’s grade-school kids may end up doing work that hasn’t been invented yet.

The contemporary American classroom, with its grades and deference to the clock, is an inheritance from the late 19th century.

So Abigail won’t be doing genetic counseling. Oliver won’t be developing Android apps for currency traders or co-chairing Google’s philanthropic division. Even those digital-age careers will be old hat. Maybe the grown-up Oliver and Abigail will program Web-enabled barrettes or quilt with scraps of Berber tents. Or maybe they’ll be plying a trade none of us old-timers will even recognize as work.

For those two-thirds of grade-school kids, if for no one else, it’s high time we redesigned American education.

As Ms. Davidson puts it: “Pundits may be asking if the Internet is bad for our children’s mental development, but the better question is whether the form of learning and knowledge-making we are instilling in our children is useful to their future.”

In her galvanic new book, “Now You See It,” Ms. Davidson asks, and ingeniously answers, that question. One of the nation’s great digital minds, she has written an immensely enjoyable omni-manifesto that’s officially about the brain science of attention. But the book also challenges nearly every assumption about American education.

Don’t worry: She doesn’t conclude that students should study Photoshop instead of geometry, or Linux instead of Pax Romana. What she recommends, in fact, looks much more like a classical education than it does the industrial-era holdover system that still informs our unrenovated classrooms.

Simply put, we can’t keep preparing students for a world that doesn’t exist. We can’t keep ignoring the formidable cognitive skills they’re developing on their own. And above all, we must stop disparaging digital prowess just because some of us over 40 don’t happen to possess it. An institutional grudge match with the young can sabotage an entire culture.

When we criticize students for making digital videos instead of reading “Gravity’s Rainbow,” or squabbling on Politico.com instead of watching “The Candidate,” we are blinding ourselves to the world as it is. And then we’re punishing students for our blindness. Those hallowed artifacts — the Thomas Pynchon novel and the Michael Ritchie film — had a place in earlier social environments. While they may one day resurface as relevant, they are now chiefly of interest to cultural historians. But digital video and Web politics are intellectually robust and stimulating, profitable and even pleasurable.

The contemporary American classroom, with its grades and deference to the clock, is an inheritance from the late 19th century. During that period of titanic change, machines suddenly needed to run on time. Individual workers needed to willingly perform discrete operations as opposed to whole jobs. The industrial-era classroom, as a training ground for future factory workers, was retooled to teach tasks, obedience, hierarchy and schedules.

When we criticize students for making digital videos instead of reading “Gravity’s Rainbow,” we are blinding ourselves to the world as it is.

That curriculum represented a dramatic departure from earlier approaches to education. In “Now You See It,” Ms. Davidson cites the elite Socratic system of questions and answers, the agrarian method of problem-solving and the apprenticeship program of imitating a master. It’s possible that any of these educational approaches would be more appropriate to the digital era than the one we have now.

To take an example of just one classroom convention that might be inhibiting today’s students: Teachers and professors regularly ask students to write papers. Semester after semester, year after year, “papers” are styled as the highest form of writing. And semester after semester, teachers and professors are freshly appalled when they turn up terrible.

Ms. Davidson herself was appalled not long ago when her students at Duke, who produced witty and incisive blogs for their peers, turned in disgraceful, unpublishable term papers. But instead of simply carping about students with colleagues in the great faculty-lounge tradition, Ms. Davidson questioned the whole form of the research paper. “What if bad writing is a product of the form of writing required in school — the term paper — and not necessarily intrinsic to a student’s natural writing style or thought process?” She adds: “What if ‘research paper’ is a category that invites, even requires, linguistic and syntactic gobbledygook?”

What if, indeed. After studying the matter, Ms. Davidson concluded, “Online blogs directed at peers exhibit fewer typographical and factual errors, less plagiarism, and generally better, more elegant and persuasive prose than classroom assignments by the same writers.”

In response to this and other research and classroom discoveries, Ms. Davidson has proposed various ways to overhaul schoolwork, grading and testing. Her recommendations center on one of the most astounding revelations of the digital age: Even academically reticent students publish work prolifically, subject it to critique and improve it on the Internet. This goes for everything from political commentary to still photography to satirical videos — all the stuff that parents and teachers habitually read as “distraction.”

A classroom suited to today’s students should deemphasize solitary piecework. It should facilitate the kind of collaboration that helps individuals compensate for their blindnesses, instead of cultivating them. That classroom needs new ways of measuring progress, tailored to digital times — rather than to the industrial age or to some artsy utopia where everyone gets an Awesome for effort.

The new classroom should teach the huge array of complex skills that come under the heading of digital literacy. And it should make students accountable on the Web, where they should regularly be aiming, from grade-school on, to contribute to a wide range of wiki projects.

As scholarly as “Now You See It” is — as rooted in field experience, as well as rigorous history, philosophy and science — this book about education happens to double as an optimistic, even thrilling, summer read. It supplies reasons for hope about the future. Take it to the beach. That much hope, plus that much scholarship, amounts to a distinctly unguilty pleasure.

NYTEducation

martes, 2 de agosto de 2011

Los medios sociales ¿fraude para la educación?

"el descubrimiento y la ciencia requieren de un pensamiento profundo, de tiempo y focalización. Los problemas complejos y enormes que enfrentan las diferentes sociedades alrededor del mundo no se resolverán con twitter, G+ o los medios sociales"

Aunque el post completo de George me parece un poco pesimista y quizá posteado sin haber reflexionado suficientemente en ello, creo que direcciona un problema que los docentes conectivistas venimos enfrentando en las aulas universitarias: el desinterés de profesores y autoridades académicas para tomar en serio a los medios sociales. En este post asumo como George, que los medios sociales comprenden entre otros a Twitter, Facebook y G+.

George escribe que los medios sociales son un asunto de flujo, no de creación intelectual. Creo que sí. Los medios sociales han potenciado la comunicación global, para bien y para mal. Twitter puede ser utilizado como lo menciona George, para llamar la atención, para denostar, difamar, engañar. Nuestros jóvenes estudiantes utilizan las redes sociales para pasar el tiempo, compartir y jugar. Las estadísticas que señalan a las mujeres adultas como un sector importante en el uso de los juegos de Facebook denotan quizás un problema de soledad.

En los sectores educativos de nivel hasta k12, las redes sociales y el conectivismo son atractivos porque el conocimiento a impartir a los educandos es generalmente menos profundo, asequible y práctico. Pero en el ámbito de la educación superior y el posgrado los medios sociales parecen una pérdida de esfuerzo y tiempo, un distractor de la atención que deben tener los estudiantes para alcanzar el nivel de concentración y profundidad requerido en sus aprendizajes.

¿Tienen entonces razón quienes defenestran el uso de Internet en las aulas universitaras?

Creo que no. Tampoco creo que George tenga toda la razón al minimizar el uso de los medios sociales en la educación superior. Estamos aprendiendo a convivir con la Internet y sobre todo con las nuevas tecnologías de comunicación e interacción. Es un asunto de flujo, sí. Interacción textual, visual, multimedia, inmediata. En las aulas universitarias la interacción Maestro-Alumno y Alumno-Alumno tienen un papel esencial, los medios sociales potencian este tipo de interacción haciendo posible la comunicación entre pares y entre aprendices y expertos de una forma global, por lo que en teoría, es posible globalizar el aprendizaje y las oportunidades.

Es un asunto de flujo, sí. El medio es el mensaje, también. Pero la inteligencia y el conocimiento, las habilidades analíticas, de reflexión, las continúan aportando las personas en forma individual o colectivamente. Y los medios son el vehículo natural para compartir conocimiento e información, para generar retroalimentación, cooperación, colaboración y crítica, el asunto de las instituciones educativas del mundo es potenciar y aprovechar estas oportunidades para mejorar nuestro mundo, es nuestra oportunidad.

Los medios sociales ¿fraude para la educación?

lunes, 18 de julio de 2011

Chao Chao Facebook

Así que ahora es perceptible un éxodo de educadores, profesionistas, profesionales, investigadores, étc. hacia G+. De momento la mayoría mantiene ambas cuentas pero el éxodo dependerá de la liberación formal de G+ y su capacidad para soportar el alud de nuevas cuentas que ya se adivina exponencial.

Los chicos jóvenes no emigrarán a G+. Son asiduos a los juegos, a pasar el rato, a compartir música, videos, fotografías, juegos, frases, divertirse. Estos chicos poco se preocupan en controlar quién recibe sus actualizaciones de estado, no les importa, lo que desean es compartir y pasar el rato y no invertir tiempo en administrar una tecnología para aprender y clasificar su privacidad y sus contactos. Pero a Facebook sí que le preocupará el éxodo de los adultos, pues son los que tienen dinero y poder de compra. Los adolescentes no compran o compran muy poco. El negocio de las redes sociales promete una guerra sin cuartel. Facebook tendrá que buscar parchar (si fuera posible) su entorno para hacer frente al nuevo invento de los círculos. Malas noticias para FB. Comenzar a modificar de fondo una tecnología es signo evidente de obsolescencia, caída en picada, como le sucedió a MySpace. "Como me ves, te verás" podría decir ahora MySpace a Facebook, un imperio amenazado. No es para menos.

Para los educadores, G+ es un nuevo juguete tecnológico que desatará nuevos experimentos de innovación educativa. Sin olvidar la guerra que se avizora por el nuevo invitado tecnológico de las redes sociales: video, voz. Un reto para todos. Desarrolladores, usuarios, tecnología. Chao Chao Facebook, tu futuro depende ahora de la competencia.

Chao Chao Facebook

domingo, 10 de julio de 2011

Ahora tengo cuenta en Google+

Desde entonces no me he separado de la computadora de escritorio. Si accedes a una nueva comunidad virtual es difícil ceder a la tentación de conectarse con los amigos, investigadores, educadores, escritores y artistas con quienes compartes tu vida y preocupaciones en la villa global de la Internet.

Soy un adicto al elearning. Una vez ingresado surge también la necesidad de conocer más acerca del entorno y su práctica ecológica con los demás que habitan el mismo espacio. Léase Facebook, Ning, LinkedIn, Twitter. Soportes móviles como tabletas (iPads) y teléfonos "inteligentes". La guerra de las redes sociales por capturar mercado en los dispositivos móviles. Google+ y Facebook aportan una vía a una era de comunicación por voz y video. Videochat. Que promete ser interesante y un desafío de la comunicación y la tecnología. Y la educación, que aún no despierta y no se entera de que existen otros medios diferentes a la relación acostumbrada profesor - estudiante.

En las discusiones de café con mis colegas de la Facultad, a veces suelo reenviar a sus correos algunos artículos que me parecen interesantes pero que no he tenido tiempo de leer, los reenvio para provocar la discusion o simplemente para compartir. Craso error local. Mas de uno me pide que defienda y exponga el contenido que les compartido como si fuese propio. Me reclaman la ligereza con que suelo compartir contenidos econtrados en la Web.

Esto me ha provocado una reflexión en mi quehacer como profesor universitario. Los profesores representan (aún) la experticidad en sus asignaturas. No pueden actuar como facilitadores de algo que no han estudiado y analizado suficientemente como para incorporarlo a su dominio de conocimientos aceptados. Uno de mis colegas afirma que el conocimiento requiere de tiempo y años antes de ser aceptado como tal y poder compartirlo en las asignaturas.

De la misma forma que rechazan el conocimiento y discusiones que surgen en la red, rechazan también conectarse con investigadores y educadores. ¿para qué? Claro. Se han formado y desarrollado su actividad en medios presenciales, duros (papel) y no estan dispuestos a experimentar. Los libros de texto en las Universidades son como las Biblias de la Educacion. Recuerdo libros de Hidráulica, Programación (llamados incluso Biblias), Inteligencia Artificial. Todos enormes que solía denominar como ladrillos del conocimiento. Toma años escribir un libro así. Un colega que suele traer bajo el brazo libros envejecidos de pedagogía, de autores clásicos, me dijo alguna vez: "no estoy dispuesto a enseñar y utilizar la tecnología de moda, no me gusta perder mi tiempo con eso".

El profesor en la aulas universitarias es el experto. Facilitar un conocimiento o enlaces a otros expertos en la red es algo inimaginable para él. Distractor de los objetivos perseguidos en las asignaturas. De su diseño instruccional que controla todo: tiempos, lecturas, aprendizaje. Las comunidades virtuales de enseñanza/aprendizaje se enfrentan a un muro conservador. Las estructuras y modelos clásicos de la educación. Los profesores mismos. Tomará decenas de años avanzar a un cambio en la formación. Esperar el cambio generacional a nuevos educadores parece natural. Sin embargo, la generacion de profesores en la actualidad enseñan como ellos han sido educados y conforme a sus principios de vida académica fuertemente integrados. Provocan que muchos egresados mantengan en su vida profesional estos mismos principios que retardan el acceso a la nueva modernidad.

La comunicación ubicua. Elearning de código abierto. La irrupción del aprendizaje y la transformación de las estructuras piramidales alrevés. Las masas deciden qué aprender con quién cuándo y cómo. Un mundo donde todos seamos aprendices y sea posible transformar el orden económico y social en que nos desempeñamos.

Ahora tengo cuenta en Google+

lunes, 27 de junio de 2011

A propósito de una cita de John Dewey

"Si enseñamos a los estudiantes de hoy como enseñábamos a los de ayer, les privaremos del mañana"

Mis colegas se oponen al uso de la tecnología en las aulas y especialmente a utilizar medios sociales como Facebook o Twitter aduciendo no querer perder el tiempo leyendo a merolicos con discusiones superficiales sobre la educación.

Transcribo algunas de las afirmaciones que me hicieron llegar de forma respetuosa:

"...para que quiero un millón, si solo se contar hasta 10..."

-Fragmento de canción popular.

"Saludando o besando manos podré llegar a formar mi conocimiento?...lo veo muy difícil.."

"...la esencia de la tecnología educativa en general es comprar lo más nuevo para que lo tonto se nos quite y podamos hacer alarde de que ahora si "conocemos", por que me he comprado el último iPhone: Te repito no compraré una Tablet, ni palm ni notebook aunque tenga que dejar de leer por aquello de que los libros impresos sean sacados del mercado, y no me inscribiré al facebook. He dicho."

"Tengo, desde hace algunos años, un enunciado que opongo a la cita que te parece tan interesante; es la siguiente:

"Los profesores formados en el pasado enseñamos a los alumnos del presente para que estén preparados para el futuro".

Si te pones a pensar un poco puedes concluir que así ha sido siempre, desde que la humanidad existe. Tengo otra:

"El conocimiento científico en un momento dado, sólo cuando es antiguo llega a ser objeto de contenido de aprendizaje en las escuelas".

Tal vez fuera conveniente que leas un poco algun libro (antes de que desaparezcan) a la vez que lees lo que tanto merolico sube a la nube".

Les agradezco la contestación, pero deseo comentar algo que pienso no conseguí expresar correctamente.

La cita de John Dewey se refiere al "cómo" y no al "qué", es decir, el medio es el mensaje.

Si le doy a un hambriento pan, calmaré su hambre por un día. Si le enseño a conseguir su propio alimento, no tendrá hambre durante toda la vida.

Esto es lo fundamental de promover el autoaprendizaje, solventar sus propios deseos de aprender y superarse sin que necesariamente tengan que depender de asistir frecuentemente a cursos formales y de actualización.

El conocimiento en general se duplica cada menos de dos años, cada vez es más dinámico, en las escuelas es preciso discutir conocimiento que está en proceso de consolidación e involucrar a los estudiantes en estos procesos, por ejemplo la educación conectivista. O bien, recientemente se descubrió que las neuronas humanas no solo emiten información por medio del axón, sino que el mismo axón también recibe información, esto trastoca todo lo desarrollado científicamente bajo el supuesto anterior, ¿debemos ocultar este hallazgo a los estudiantes o involucrarlos en la discusión global y los estudios realizados?

Mi opinión personal es que la escuela como una entidad controlada por un pequeño grupo de docentes autorizados no tiene razón de permanecer así, desconectada de las discusiones globales en torno al conocimiento.

De acuerdo, los merolicos retan a los científicos, crean Wikipedia, publican en blogs y no en revistas indexadas, discuten en foros de Internet, no en Congresos costosos e inalcanzables y demás reuniones apresuradas, comparten inmediatamente posiciones y opiniones, la imperfección natural de los investigadores, la inmediatez, las dudas, los hallazgos, convirtiendo así el conocimiento y la educación en un dominio público y no privado.

Los libros ya publicados se digitalizan, no desaparecen, pero dudo mucho que los libros del futuro se divulguen en papel, hoy mismo, un escritor de la ciudad de Los Angeles postea en un blog que dejó de publicar por medios tradicionales, donde tiene que pagar a un agente, un editor, la distribucion, pierde los derechos a publicar extractos de su libro, su libro anterior cuesta impreso 17 dolares y su nuevo libro digitalizado por él mismo como EPUB, lo cargó él mismo a sitios de Internet como AMAZON y otros, donde se vende ahora a 2.5 dolares digitalizado, gana mucho mas, vende mucho mas y es leido mas ampliamente por mas personas.

¿Qué sucede con ésto? Que se derrumba un mundo basado en el papel, que trastorna las economías que no están preparadas para ello, los empleos, las profesiones, las imprentas, los talamontes, las librerías, la educación, la cotidianeidad social densamente conectada, el docente como fuente principal de conocimientos en el aula, el modo de trabajar.

Las tecnologías por sí solas no transforman nada, sino es el uso que les damos, los ahora estudiantes trabajarán y vivirán en un mundo altamente conectado donde la tecnología estará presente en la casi totalidad de sus actividades cotidianas, conformando un nuevo lenguaje, un nuevo habitat, para el que se requieren habilidades y el desarrollo y aceptación de una ciudadanía digitalizada.

Los educadores de hoy, deberán ser capaces de incorporar el lenguaje tecnológico en todas sus asignaturas, no hacerlo, es dar por hecho que el futuro de los jóvenes será el mismo mundo en que nos nosotros nos desarrollamos y habitamos sin Internet, sin comunidades globalizadas conectadas, sin tecnología. Lo cual es un error.

¿Usted, qué opina?

A propósito de una cita de John Dewey

domingo, 26 de junio de 2011

El rechazo de los educadores a las redes sociales

Los jóvenes estudiantes de quienes tanto se quejan los adultos por "perder" su tiempo en las redes sociales, aprenden a dominar un nuevo lenguaje tecnológico para compartir y aprender. Si bien ahora suelen llamarlos huérfanos digitales porque crecen en los medios sociales electrónicos sin ninguna guía que los oriente, confío plenamente en que cuando estos chicos sean profesionistas, utilizarán los medios sociales digitalizados para trabajar, aprender y compartir de una manera trascendente que no podemos describir ahora dado el rápido avance de las tecnologías y de la Inteligencia Artificial, no me cabe la menor duda que se transformará el modo del quehacer y convivir,

El rechazo de los educadores a las redes sociales

jueves, 23 de junio de 2011

Cursos Abiertos y Masivos En Linea

La Universidad de Illinois en Springfield anunció un Curso Abierto Masivo y En Linea sin créditos, dedicado a examinar el estado actual de la educación en línea y hacia dónde se dirige el futuro del e-aprendizaje. Cerca de 500 personas de dos docenas de países se han registrado y se espera el registro de mil más cuando dé inicio el curso abierto el próximo lunes.

Este curso forma parte de una nueva tendencia a la educación abierta. Fuente:

http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/u-of-illinois-at-springfield-offers-new-massive-open-online-course/31853

Cursos Abiertos y Masivos En Linea

lunes, 20 de junio de 2011

La investigación en la Universidad

El privilegio es meramente personal, individual, ni siquiera colectivo. Nuestro gremio está contaminado por el control que ejercen nuestros superiores, nuestros empleadores, nuestros directivos, los administradores de la función académica, los hombres de escritorio.

El día a día es complejo, continuamos con la actitud de vivir inmersos en una selva llena de riesgos y peligros, para sobrevivir. Pero lo peor de lo peor de lo peor es la lucha interna, entre nosotros mismos. El servilismo, la simulación, el conservadurismo, la investigación tradicional, el engaño, incluso.

Nuestros investigadores no innovan, no son creativos, no arriesgan, se han convertido en académicos llena papeles y formatos. Cuando hacia el doctorado en europa los jóvenes investigadores se quejaban de sus asesores: la investigación se termina cuando se publica un reporte. Los investigadores deben cumplir con publicación de reportes cada cierto tiempo para demostrar su actividad.

Esto ha invadido mi quehacer doméstico, en México. No tengo libertad. Estoy sujeto a control. Trabajo en una Universidad Pública como profesor-investigador pero estoy sujeto a las decisiones superiores. No vale el perfil académico con que se me ha contratado. Los controles y filtros académicos son abundantes y crecientes.

Las instituciones de educación superior tienden a controlar minuto por minuto las actividades de sus empleados, en lugar de privilegios, parecemos esclavos modernos, nuestros ingresos económicos dependen de la obediencia, nos manejan como si fueramos autómatas programables, ellos deciden cómo debemos escribir, cómo investigar, con quién investigar, qué investigar, en dónde publicar, y nos inundan de formatos en los que estamos obligados a mentir si queremos sobrevivir.

Esta es la vida que llevamos donde "los que tienen mas saliva tragan mas pinole", es un dicho que retrata la corrupción académica en la Universidad. Las mafias de poder conformadas por nosotros mismos. El incesto académico, el proteccionismo, la defensa de un status y el amor al dinero, para vivir mejor. Esto es uno de los motivos por los que alguien que deseaba ilusioriamente formar parte de una institución de privilegio, desea ahora encontrar un modo de apartarse, para poder investigar sin restricciones, pero hay algo, ¿de qué voy a vivir?

La investigación en la Universidad

viernes, 10 de junio de 2011

Internet y los adultos mayores

Otro punto de vista opuesto sugiere que utilizar la Internet acarrearía mayores problemas e inconvenientes a los adultos mayores y que debería dejárseles en paz y no molestarlos con esta insistencia a vivir conectados en este periodo de sus vidas. Una de las preguntas posibles es ¿hace la Internet más fácil o cómoda sus vidas? Quizás en términos de encontrar información o ver las noticias pero no necesariamente conectadas podría ser provechoso.

En México es conocido que al interior de muchas familias de clase media algunos miembros no precisamente mayores no han utilizado nunca alguna computadora o tampoco han accedido alguna vez a la Internet. Aún cuando existan computadoras conectadas a Internet, la madre o también el padre no manifiestan ningún deseo de conectarse o buscar información, para ellos la televisión, la radio, los periódicos y el teléfono son suficientes para sobrellevar y controlar sus vidas. Sin embargo la manifestacion en todos los medios y entornos familiares de uso de tecnologías puede interpretarse como un acoso generalizado que provoca intranquilidad y la generación de una especie de bloqueo mental a todas estas manifestaciones de la nueva sociedad.

Existen muchas personas que han desarrollado toda su vida sin utilizar computadoras o Internet en todos los ámbitos de su desempeño social y laboral. En las Universidades muchos investigadores, profesores y funcionarios continúan sus vidas aparentemente normales dentro de un entorno invadido por tecnología. Es indudable que la tecnología ha invadido su entorno laboral y familiar propiciando una negación o bloqueo mental para protegerse de tener que adaptarse a un mundo invadido de tecnología fija y móvil que no estaba prevista en sus expectativas.

Es cierto que existen personas mayores que disfrutan de la conectividad por medio de Internet y que abrazan con la curiosidad de un niño que recibe juguetes nuevos el uso de las TICs para informarse o conectarse.

En el caso de los educadores que rechazan incorporar tecnologías no solo se privan ellos mismos de todas las ventajas inherentes a la conectividad y el acceso a fuentes múltiples de información sino que afectan el desempeño de sus estudiantes que accederán a un mundo altamente conectado e informado para el cual no han sido preparados formalmente, he allí el peligro.

Internet y los adultos mayores

miércoles, 25 de mayo de 2011

Inteligencia Artificial en la Educación

http://iaied.org/about/

La siguiente direccion es de la revista:

International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education

http://iaied.org/journal/about/

Existe una Conferencia bienal (cada dos años) llamada

AIED

En el 2011 se llevará a cabo la siguiente Conferencia

Internacional de la Inteligencia Artificial en la

Educacion. AIED 2011

http://iaied.org/conf/event/4/

Esta Conferencia se distingue por enfocarse en el

desarrollo de modelos computacionales sobre aspectos

relevantes en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje.

Una de las ideas centrales de la Inteligencia Artificial

en la educacion, ha sido desarrollar sistemas computacionales

para el soporte del aprendizaje que mantengan una

conexion cercana al desarrollo de modelos y

arquitecturas cognitivas. Es decir, algo asi como

Ciencia Cognitiva Aplicada.

Lo anterior implica un rigor metodologico en la evaluacion

de los ambientes soportados para el aprendizaje inteligente.

En los ultimos años los aspectos motivacionales han

recibido considerable atencion y los escenarios para el

aprendizaje han sido concebidos como socialmente

contextualizados.

Inteligencia Artificial en la Educación

sábado, 21 de mayo de 2011

¿Tiene sentido la existencia en el futuro de los libros?

En la actualidad la información la obtenemos mediante la Internet, podemos mantenernos actualizados casi en tiempo real, enterarnos de sucesos mediante cámaras móviles que se suceden al mismo instante en que ocurren, cada vez son más los investigadores que reflexionan en blogs, encuentros virtuales, foros y sitios de Internet, el día a día de sus descubrimientos e investigaciones.

La colaboración, comunicación y divulgación de esta información alcanza también a los estudiantes, curiosos o interesados en ello.

¿Tiene sentido esperar la permanencia de los libros como tales en el futuro mediato? Si podemos enterarnos casi instantáneamente de los sucesos novedosos en nuestro dominio de conocimientos, si comienza a entenderse el mundo de la divulgación científica como burocrático e inoperante, ¿tienen sentido las historias completas que son el fundamento de los libros, si cada lector puede generar su propia historia, desaparecerán los libros?

¿Tiene sentido la existencia en el futuro de los libros?

domingo, 15 de mayo de 2011

Mobile Computing: A 5-Day Sprint

The EDUCAUSE Mobile Computing 5-Day Sprint has come to an end, but the conversation will go on. We'll continue to explore what mobile computing means for the future of higher education through on-going EDUCAUSE Live! webcasts, resources, and community discussions.

[Enlace]

Mobile Computing: A 5-Day Sprint

Mundos Virtuales: el desplome de Second Life (en inglés)

Durante tres largos años mantuvimos un proyecto en Second Life que fue mutando en cuanto no fuimos capaces de obtener apoyos para mantenerlo. Abandonamos el proyecto en enero de 2011.

El siguiente artículo (en inglés) es interesante porque desvela el desplome no anunciado y no deseado del mundo virtual de Second Life. OpenSim no termina de mostrarse competitivo y Second Life es una especie de guia y comparativo para los nuevos mundos virtuales que se desarrollan.

Una de las causas de este desplome es la tecnología, aún no estamos en condiciones tecnológicas de soporte para banda ancha generalizada y el boom de las redes sociales ha generado una atracción masiva que hace que los usuarios potenciales pierdan interés de incursionar en los mundos virtuales. Educadores y estudiantes se vuelcan a las redes sociales para experimentar nuevos enfoques pedagogicos y de comunicación.

A pesar de todo, Second Life se mantiene porque es estable es el líder y (todavía) es "lo mejor que hay".

[Enlace]

Mundos Virtuales: el desplome de Second Life (en inglés)

El Educador Conectado en Chilpancingo, Gro.

Un saludo a mis amigos y colegas de la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional

campus 12a en la ciudad de Chilpancingo, Guerrero donde participo ahora

como invitado al taller del Educador Conectado y donde me siento feliz

de poder colaborar en el apoyo a docentes para incorporar las tecnologías

de Internet en el quehacer académico y la vida diaria.

Les envío un saludo afectuoso y mi ofrecimiento de que pueden contar

conmigo en las redes sociales, y personalmente cuando sea posible

de ahora en adelante, en este camino sinuoso de incorporarnos a las

tecnologías de Internet para descubrir lo maravilloso que resulta

acceder y estar permanentemente informados de aquéllo que a cada uno

de nosotros es de interés.

Feliz día del Maestro, hoy y siempre.

Un fuerte abrazo.

Edgar

-----------------------------------------------------------

El Educador Conectado en la Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero

El miércoles daré nuevamente la charla "El Educador Conectado" pero ahora

en la Unidad Académica de Economía de la Universidad de Guerrero, una Facultad

que me ha invitado más de una vez a impartir charlas, como aquélla primera

que recuerdo gratamente sobre el uso de los mundos virtuales en la educación.

Este miércoles 18 a las 11 horas daré la charla de El Educador Conectado en el

auditorio de la Unidad Académica de Economía. En esta plática dirigida a

estudiantes, profesores e investigadores intento explicar cómo pueden

mantenerse actualizados en el ejercicio de su profesión mediante las

tecnologías de Internet. En el pasado solíamos visitar las bibliotecas y

algunas librerías, conseguir artículos de investigación, consultar a los

profesores, estar pendiente de las noticias, asistir a talleres de

actualización, realizar estudios de posgrado, o buscar en Internet

nueva información relacionada con nuestro dominio de interés.

En este nuevo siglo se populariza otra forma de aprender en Internet,

basada en mantener una Red Personal de Aprendizaje (RPA), los chicos estudiantes

conocen muy bien dinámica al utilizar Facebook y me valgo de este ejemplo para

explicar esta dinámica, cuando un joven postea una fotografía, un enlace, algún

comentario, pregunta o dice algo, todos sus contactos en Facebook se enteran

de forma automática y pueden si así lo desean acceder a los enlaces que se

proporcionan, el que postea no debe preocuparse como antaño en buscar y

especificar los destinatarios de la nueva información. Hasta hace pocos años,

utilizabámos el correo electrónico para compartir información, ahora, si

contamos con cientos o miles de contactos no tenemos que recordar o direccionar

correos personalizados, las conexiones de las redes sociales y la tecnología

RSS hacen posible utilizar las redes sociales y crear redes de blogs con el

mismo fin, además, no necesitamos realizar búsquedas en Internet sino que

la información nueva llega a nosotros mediante RSS, la herramienta READER de

google se encarga de recolectar la nueva información de los nodos de Internet

a los que nos hayamos suscrito mediante RSS.

Es decir, el uso de Internet en la vida cotidiana marca un antes y un después

en la forma en que recuperamos información. Un antes y un después para las

generaciones que nos formamos sin Internet y las nuevas generaciones. Los

educadores formados con el paradigma anterior perjudicamos a los estudiantes

ignorando estas nuevas formas de acceso y actualización disponibles en todo

lugar donde existan conexiones a Internet, que cada día son mayores y la

facilidad de acceso es móvil y permanente.

El enlace siguiente ofrece una versión anterior de esta charla cuando la

presenté por primera vez, ahora es también la introducción al taller que

ofrezco para docentes de todos los niveles educativos, cuando ésto sea posible.

[Enlace]

-------------------------------------------------------

Do you Welcome Mobile Devices in the Classroom?

¿Los profesores construirán una pedagogía móvil y deben motivar a los estudiantes

para que utilicen dispositivos móviles?

[Enlace]

Usted puede participar en esta discusión en IdeaScale (en inglés):

[Enlace]

------------------------------------------------------

El Educador Conectado en Chilpancingo, Gro.

sábado, 29 de enero de 2011

sábado, 22 de enero de 2011

Conectivismo en la Educación Superior

definen un proyecto que podría ser su trabajo de titulacion y se dedican a

investigar y definir lo que podría ser su protocolo de tesis o proyecto de

titulación.

Esta asignatura resulta atractiva para explorar el uso del conectivismo en

la educación superior. Los estudiantes trabajan a partir de una red personal

de aprendizaje y especialmente el uso de blogs personales para describir sus

avances en el proceso de la exploración conectivista en Internet. Utilizamos

Facebook para mantenernos como grupo y compartir ideas y preguntas e intentar

promover la discusión fuera de línea sobre temas que los mismos chicos

plantean. Asimismo los estudiantes intentan establecer conexiones en Internet

con nodos relacionados con sus temas, esto es, incorporarse a comunidades de

interés y participar en la medida de lo posible en el aprendizaje y discusión

de temas relacionados con su trabajo de investigación.

Estas conexiones podrían darse libremente en redes sociales como Facebook,

LinkedIn, Ning, Blogs, Twitter, Slideshare, sitios para compartir videos,